URLs and the Semantic Web

Written by: Allie Tatarian

JSON-LD, RDF, and other technologies mentioned in the MetaSat primer are all part of the semantic web. The semantic web is a set of standards defined by the World Wide Web Consortium with the goal to make data on the web easily shareable and machine-readable. Right now, humans can connect with other humans through the world wide web, and humans can interact with data and software programs. However, it can be difficult for machines and programs to communicate with each other without a human directing the interaction. Semantic web technologies propose to make this task easier, which will help improve the distribution, proliferation, and interpretation of data.

That being said, in order to share data effectively, it must be paired with excellent metadata. Metadata is data about data, such as where it is from, what it is measuring, who created it, and more. In order for metadata to be interoperable, metadata fields should be represented by unique, permanent identifiers. Unique identifiers are necessary and helpful to define ideas. Identifiers can vary a lot, and some things have multiple different kinds of identifiers. For example, you might be identified by your name, your address, or your national identification number (Social Security number in the US). Your name and address, however, while they might be useful in most cases, are not unique, permanent identifiers. There may be other people who have your same name, and other people who live at your address. Your name and address may change over time. But your Social Security number stays the same your entire life. Your name, address, and SSN are all identifiers, but only your SSN acts as a unique, permanent identifier.

On the semantic web, metadata is structured according to a standard called the Resource Description Framework (RDF). The RDF model stores metadata in subject-predicate-object triples. For example, to describe the title of this book, the RDF triple might look like "This book (subject) has title (predicate) The Hunger Games (object)." This works a little differently than natural languages, so that sentence may sound a little weird, but it makes sense to machines that know RDF.

However, computer programs do not know the definitions of words, so we have to tell them what they are. To do this, we can use URLs to represent both the thing we are describing (the book) and the metadata we are trying to record (the title). In this case, we could use the Goodreads link to represent the book and a term from schema.org to represent the title. The more machine-friendly RDF triple becomes "https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2767052-the-hunger-games (subject) https://schema.org/name (predicate) The Hunger Games (object)"

This is obviously not how most people usually use URLs to navigate the web. Why does this work, and how do machines use URLs differently than people do?

What URLs are

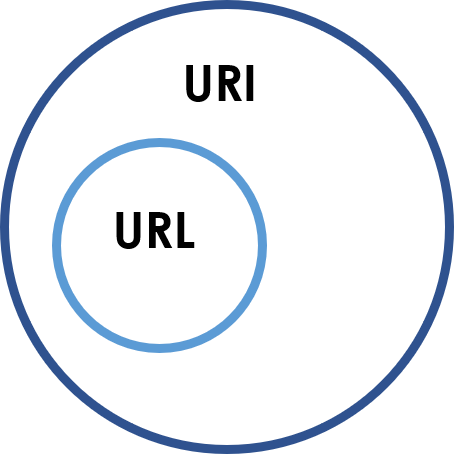

URL stands for "Uniform Resource Locator." It is a type of URI, or "Uniform Resource Identifier." A URI tells you what something is, and a URL tells you where to find it on the web. A URI can act as a unique identifier for a topic, since a URI acts as an identifier for a resource. A URL, on the other hand, is a location, telling your computer where to find a resource; it acts like an address that tells your browser or program where it can find something. Every URL is also a URI, which means that it is an identifier, but may or may not be a unique, permanent identifier. That's what you can see in the Venn diagram below: Every URL is a URI, but not every URI is a URL.

When you input a URL into your web browser, your machine makes what is called a GET request to another machine called a server. Before it can make the GET request, however, the URL has to be converted into something the server understands: an IP address. Each URL is essentially a stand-in for an IP address. This is why multiple URLs can point to the same page: They can all stand-in for the same IP address. For example, both "nytimes.com" and "newyorktimes.com" point to the IP address assigned to the New York Times' website. This is called a redirect—a different URL than the "main" one can direct to the same page. This is how services like TinyURL and Bitly work—the URL they give you redirects to the original URL that you put in.

When a server machine is given a GET request and an IP address, it then finds the proper webpage and returns it to the requesting machine. However, there is another piece of the puzzle that can complicate things. Not only can multiple URLs stand in for the same IP address, but one URL/IP address can actually point to more than one resource. This is possible because when your browser sends along an IP address for a GET request, it actually sends along additional information that the server may find helpful. For example, it may send along your browser's default language, so that the server can return a page in a language that you can read. This is called content negotiation. To sum up, with redirects, several URLs can point to the same page; with content negotiation, one URL can point to multiple web pages.

RDF, metadata, and content negotiation

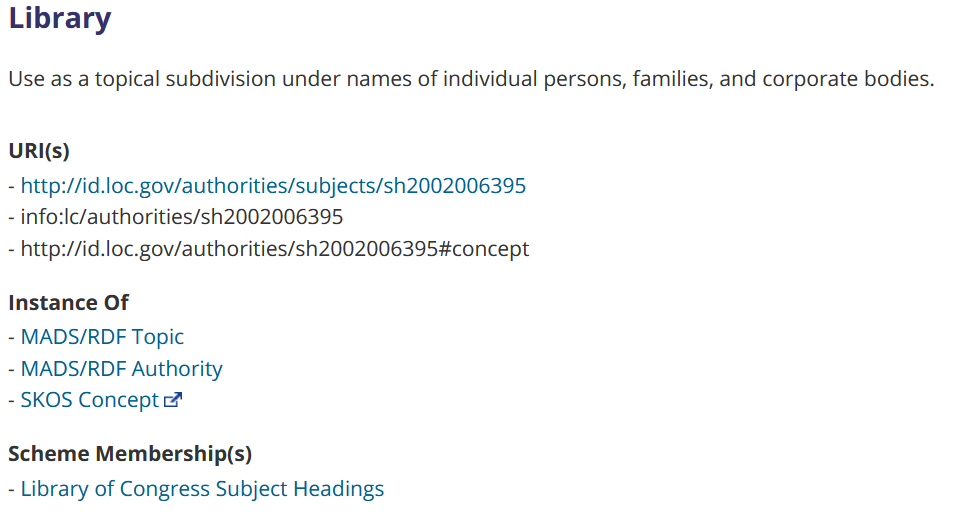

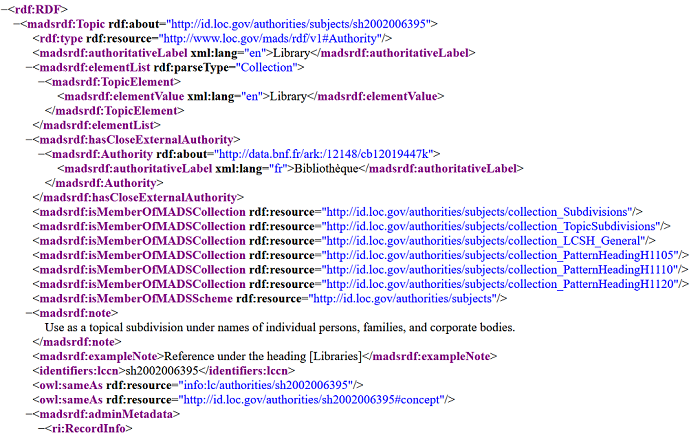

What does content negotiation have to do with metadata on the web? Well, sometimes one URL can point to different types of pages based on whether a human or a program is viewing the page. For example, one URL can point to an HTML page if a human is viewing in a browser, but point to an RDF/XML page for a program that is looking for metadata. Here is an example of the same information in two different formats (in this case, the Library of Congress Subject Heading (LCSH) for "Library"):

The first screenshot is the information in HTML, and the second is in RDF/XML. Crucially, these two pages both contain the exact same information and can be reached through the same URL (http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh2002006395). If you check the link in a browser, it will probably show you the HTML page, because browsers prefer HTML. However, if a program that prefers RDF/XML were to follow the same link, it will be shown the RDF/XML page.

(As a side note, this page also exhibits redirects. At the top of the HTML page, you can see that there are three URIs that point to this page: http://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh2002006395, info:lc/authorities/sh2002006395 (a URI that is not a URL), and http://id.loc.gov/authorities/sh2002006395#concept)

Programs like APIs that use linked data prefer formats such as RDF/XML, N-Triples, and JSON to HTML because they are much more structured and predictable than HTML. An HTML page has a lot of information in it that is not the information of interest to a program. For example, the LCSH "Library" page has a header, footer, search bar, navigation bar, and many links full of information that an API will probably not need. The HTML page also includes information about formatting that is important for the information to be clear to a human reader, but that will be superfluous to a program. Formats like RDF/XML strip out all of the unnecessary information so that a program will only see the data that it needs. Additionally, these non-HTML formats are often standardized, so a program will know exactly where and how to look for the data that it needs.

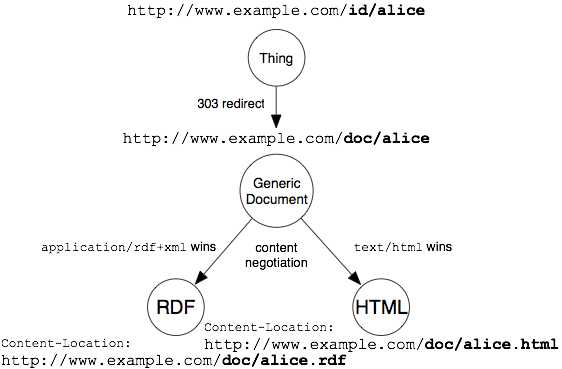

The process a program makes when choosing between different files at the same web address is illustrated in this chart from the W3C:

First, the inputted URI is redirected to the address where the main web page lives, and then the program uses content negotiation to choose between an HTML file and an XML file.

Linked data vocabulary URLs help make structured data even more useful to programs and machines, because they give a standard definition of a topic. For example, an API does not know what "title" means, and different databases may use different terms than "title" (such as "name" or "245" for MARC records). For clarity, a linked-data database may instead use a term like https://schema.org/name, which has a standard definition that will not vary and can be used in the same way throughout different databases.

Ultimately, using linked data vocabularies and excellent metadata standards is necessary for creating 5-Star Open Data, the gold standard to shareable data on the web. The MetaSat team recommends storing linked data using JSON-LD, a flexible form of RDF that is easy for humans to write and machines to read. For more on linked data and JSON-LD, see our RDF and JSON-LD primers.